In these lessons, students will be introduced to the world that Shakespeare lived and wrote in. This will help them to build an informed overview of the social and historical contexts important to the dramatic world. Tasks include: exploring how Shakespeare adapted his source material, including developing smaller roles like Mercutio; researching the London of Shakespeare's time; and imaginative writing accounts.

In order to benefit fully from these lesson plans, we recommend you use them in the following order:

- Text in Performance

- Language

- Characters

- Themes

- Contexts

If students are new to the play, we suggest you start with these introductory KS3 Lesson Plans. If you would like to teach the play in greater detail, use the advanced KS4/5 Lesson Plans.

These lesson plans are available in the Downloads section at the bottom of this page. To download resources, you must be logged in. Sign up for free to access this and other exclusive features. Activities mentioned in these resources are available in a separate downloadable 'Student Booklet', also at the bottom of this page. The 'Teachers' Guide' download explains how best to use Teach Shakespeare and also contains a bibliography and appendices referencing the resources used throughout.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I research Shakespeare’s life with a particular focus on the 1590s when Romeo and Juliet was written and first performed?

Can I put forward my views confidently and convincingly in a class debate?

Key words: argument, author, biography, contemporary, counter-argument, debate, motion, portrait, research

Prologue: Opening Discussion

Despite being a well known name in literature, Shakespeare doesn’t have a very well known face! There is some conjecture as to what the Bard actually looked like. Students imagine they have been asked to choose a portrait to be used as the front cover of a new book about Shakespeare. They can then look up various pictures of Shakespeare online and choose the one which they would like to use for the cover. Have a feedback session where students will argue the case for their chosen picture, with pros and cons. Then vote on which cover to use. Below is an example of a picture they may use and its respective pro and con:

The Droeshout portrait

Pro: Fellow playwright Ben Jonson said this portrait was a good likeness of Shakespeare.

Con: Ben Jonson may not have actually seen this portrait.

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) Why study Shakespeare?

The idea is to open up a broad, frank and open-ended discussion about Shakespeare. This kind of activity could work very well as an orientation exercise at the beginning of a unit of work.

Some ideas:

- Students could be shown ‘My Shakespeare: a new poem by Kate Tempest’ (youtube.com/watch?v=i_auc2Z67OM) and discuss the ideas raised in it.

- Students could gather the viewpoints of other students, ex-students, teachers and others in relation to studying Shakespeare.

- Students could create a large collage about Shakespeare’s continuing influence on our language and in our lives today.

- Students could write their expectations about studying Shakespeare on slips of paper to be returned to them at the end of the unit. Students could then compare their predictions with their actual experiences!

2) Timeline

Students are shown a timeline of Shakespeare’s life. It divides Shakespeare’s life into: Early Years (1564-1589); Freelance Writer (1589-1594); The Lord Chamberlain’s Man (1594-1603); The King’s Man (1603-1613); Final Years (1613-1616). Students ‘zoom’ in on the portion of Shakespeare’s life when Romeo and Juliet is written and performed and extract some key pieces of information for a Romeo and Juliet in context fact file. They should find information about biographical and historical events, the existence of the Globe and other London theatres, and other works by Shakespeare.

3) Debate

The class prepares and holds a formal debate. The motion is “The more we discover about Shakespeare the man, the more we can appreciate Shakespeare the playwright” and students should spend some time researching and planning their contributions. The class appoints a chair and the motion is proposed and opposed by the first pair of speakers, before a second member of each team also has the chance to add to their team’s case. Points and questions can then be taken from the floor, before the opposing and proposing teams sum up and a vote takes place.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

What do I know about Shakespeare’s life and times around the time he wrote Romeo and Juliet?

How did I find these things out?

How important do I think it is to know about a writer’s life in order to understand and enjoy that writer’s work?

What are some of the counter-arguments to this position?

Suggested plenary activity…

Students write up their own view about the motion discussed, taking into account the arguments and counter-arguments they have heard.

Asides: Further Resources

- Students might like to read about the latest portrait to be found that may or may not be Shakespeare, an image found in a botanical book called The Herball from 1598: telegraph.co.uk

- Students might be aware of controversies about Shakespeare’s true identity and whether he wrote all of the plays! The film Anonymous and book Contested Will are useful sources about these debates.

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

Students’ debate speeches and other contributions could be assessed for speaking, listening and writing too.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I investigate Shakespeare’s influences and inspiration for Romeo and Juliet?

Can I explain how Shakespeare made the story his own?

Key words: characters, influence, inspiration, prose, source, sympathy, tragedy, verse

Prologue: Opening Discussion

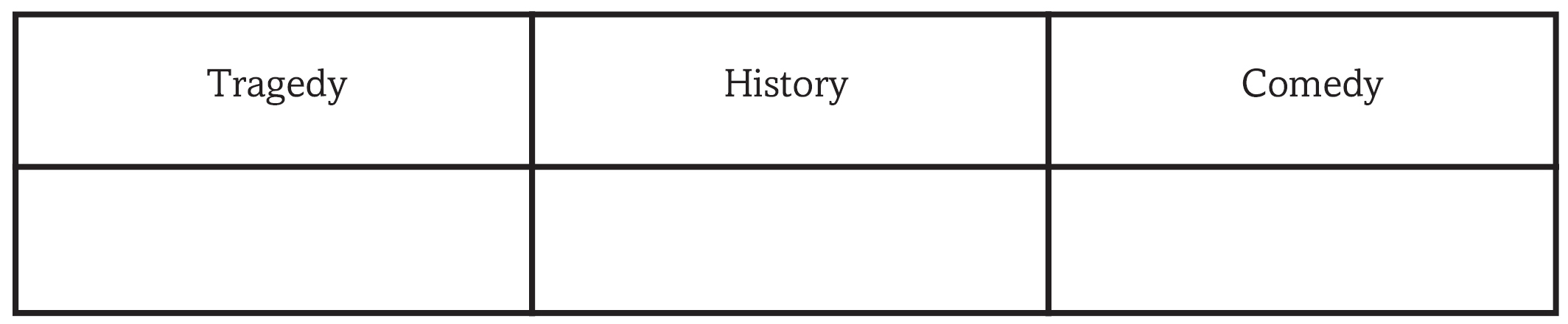

Check students’ understanding of the word genre and of the different genres of Shakespeare’s plays. Explain that Romeo and Juliet is classified as a ‘tragedy’. Ask students to fill in the following table in the Student Booklet with their ideas about Romeo and Juliet in relation to any of these three Shakespearean genres. What do students know about Romeo and Juliet that makes it a tragedy? Can students think of anything about Romeo and Juliet that is comical or historical?

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) Romeus and Iuliet

Explain to students that Shakespeare’s primary source for Romeo and Juliet was a poem by Arthur Brooke dating from 1562: ‘The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Iuliet’. Students could read the sonnet entitled ‘The Argument’ (available in the Student Booklet), with which Brooke begins his poem:

Love hath inflaméd twain by sudden sight,

And both do grant the thing that both desire

They wed in shrift by counsel of a friar.

Young Romeus climbs fair Juliet's bower by night.

Three months he doth enjoy his chief delight.

By Tybalt's rage provokéd unto ire,

He payeth death to Tybalt for his hire.

A banished man he 'scapes by secret flight.

New marriage is offered to his wife.

She drinks a drink that seems to reave her breath:

They bury her that sleeping yet hath life.

Her husband hears the tidings of her death.

He drinks his bane. And she with Romeus' knife,

When she awakes, herself, alas! she slay'th

Ask students for their comments about this text. Do they notice anything different about the plot (and in particular the play’s time frame) compared to Shakespeare’s later version? How might they explain this change from a dramatic point of view? Brooke’s complete poem can be read here: shakespeare-navigators.com/romeo/BrookeIndex.

2) Rhomeo and Iulietta

Another likely source for Shakespeare’s play was a work of prose by William Painter called ‘The Palace of Pleasure’ (1575). This featured the popular story of the two lovers among many other Italian and French stories retold in the English language. Students could read the following brief introduction to Painter’s retelling of the story, which can be found in the Student Booklet:

'The goodly Hystory of the true, and constant Loue between Rhomeo and Iuleitta, the one of whom died of Poyson, and the other of sorrow and heuinesse: wherein be comprysed many aduentures of Loue, and other deuises touching the same.'

Ask students for their comments about this text. Students could research either of these two source texts in more detail, looking for examples of similarities and differences with Shakespeare’s version. Painter’s entire work can be read here: gutenberg.org/ebooks/34840.

3) Making the story his own

One of the ways in which Shakespeare adapted his source material was to develop some of the minor characters, such as Mercutio, Paris, the Nurse and the servants. Ask students to discuss briefly in pairs what each of these characters contributes:

- to the plot itself

- in other ways (e.g. language, comedy, establishing context)

To what extent would the play be poorer without them?

Another way in which Shakespeare altered his sources was by presenting Romeo and Juliet in a positive light. Meanwhile Brooke describes his protagonists as:

'a couple of unfortunate lovers, thralling themselves to unhonest desire, neglecting the authority and advice of parents and friends, conferring their principal counsels with drunken…gossips attempting all adventures of peril for the attaining of their wished lust and abusing the honourable name of lawful marriage'

Ask students to discuss how the play might be different if Shakespeare decided – like Brooke – to present the behaviour of Romeo and Juliet in a more disapproving, negative way?

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

What inspired and influenced Romeo and Juliet?

How did Shakespeare adapt and shape his sources and influences to make them his own?

Why did he do this?

Suggested plenary activity…

Students think about what it would be like to watch a performance of Romeo and Juliet in Shakespeare’s time. Students should explain in their own words something about the play that would be exciting and something about the play that would be topical. They should also choose one more adjective of their own and justify that choice.

Aside: Further Resource

- The Italian settings of many of the stories in ‘The Palace of Pleasure’ inspired much Renaissance drama. Students could research this further, drawing links with other plays by Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

The Key Stage 4 materials under Historical and Social Context contain a more detailed and in-depth comparison of Shakespeare with his source texts, including a direct comparison of extracts.

Key Questions for Students

Can I establish how much I know about London in Shakespeare’s time and what I would like to find out?

Can I apply what I have learned in a creative task and ‘step into the shoes’ of someone visiting the theatre in Shakespeare’s time?

Key words: atmosphere, empathy, glossary, questions, research, sources, topics

Prologue: Opening Discussion

Explain to students that over the next two lessons they are going to travel back in time to the 1590s, to one of the very first productions of Romeo and Juliet. London was by far the biggest town in England and an attractive place to young men like William Shakespeare, who arrived there to make his fortune some time between 1592 and 1594. Create a brainstorm from students’ prior knowledge and impressions of London at this time.

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) Shakespeare's London

Students work in small groups discovering information about London life in Shakespeare’s time on a particular topic assigned to them. The topics are:

- entertainment;

- crime and punishment;

- transport;

- shops and trades;

- clothing;

- buildings;

- poverty;

- hygiene;

- risks and dangers.

2) Theatre Glossary

Explain that theatres were outside the walls of the City of London on the south bank of the River Thames. This meant that they were outside the jurisdiction of the Puritan city fathers. Here people would find bear pits, brothels and theatres. The Globe Theatre was built in 1599.

Students are going to compile their own glossary about theatres in Shakespeare’s time, the template for which can be found in the Student Booklet. Divide up the words among the group and ask them to predict what they think the word means in the context of Shakespeare’s theatre before looking it up here: shakespearesglobe.com/discovery-space/adopt-an-actor/glossary.

attic, cabbage, discovery space, frons scenae, gentlemen’s boxes, groundlings, heavens, hell, iambic pentameter, jig, lord chamberlain’s men, in the round, lords’ rooms, musicians’ gallery, pillars, thrust stage, ring house, traps, vomitorium, yard

Take feedback from students, including hearing about words that have a specific meaning in this context, but which have a different or more general meaning outside this context.

3) Publicising the play

Students should imagine that they are trying to sell tickets for Romeo and Juliet to passers-by on a rainy afternoon in the 1590s. How can they encourage people to come inside the theatre to see Romeo and Juliet? Students should devise publicity slogans and share them. If students have time, they could turn their slogans into printed handbills for homework.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

What would the atmosphere have been like on Bankside in this period?

What do I think drew people to the theatre?

What do I think were the challenges involved in putting on a play?

Suggested plenary activity…

Divide students into groups of three, with each student taking on a different role. Students apply what they have learned today to an empathy task in which they wonder about what it would be like to be an actor, a ticket-seller and a playwright just before the show begins. If there is time, one or two groups could perform their role plays.

Aside: Further Resource

- The cloze activity in the Student Booklet will help students build a picture of what a visit to the theatre in Shakespeare’s time would have been like. Answers are provided in the Lesson Plan download at the bottom of this page.

By 1600 London theatres could take up to ____1_____ people for the most popular plays. With several theatres offering plays most afternoons, this meant between ____2_____ and 20,000 people a week going to London theatres. With such large audiences, plays only had short runs and then had to be replaced. Between 1560 and 1640 about 3,000 new plays were written. To attract the crowds, these plays often re-told famous stories from the past, and they used violence, music and humour to keep people’s attention. This was vital because, if audiences didn’t like a play, they made their feelings known. In 1629, a visiting French company were hissed and ____3_____ from the stage. This was because the company used ____4_____ to play the female roles, something which outraged the audience.

In open air theatres the cheapest price was only 1 penny which bought you a place amongst the ____5_____ standing in the ‘yard’ around the stage. (There were 240 pennies in £1.) For another penny, you could have a bench seat in the lower galleries which surrounded the yard. Or for a penny or so more, you could sit more comfortably on a cushion. The most expensive seats would have been in the ____6_____. Admission to the indoor theatres started at 6 pence.

The groundlings were very close to the action on stage. They could buy food and drink during the performance – ____7_____ (apples), oranges, nuts, gingerbread and ale. But there were no ____8_____ and the floor they stood on was probably just sand, ash or covered in ____9_____.

In Shakespeare’s day, as people came into the theatre they had to put their money in a ____10_____. So the place where audiences pay became known as the box office.

advertising afternoon banner bottles box cushion groundlings stage tobacco toilets trumpets wage

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

This lesson is designed to prepare students for the imaginative writing task in the next lesson.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I establish how much I know about visiting the theatre in Shakespeare’s time and what I would like to find out?

Can I imagine and describe what it would have been like to be an audience member at an early performance of Romeo and Juliet?

Key words: atmosphere, empathy, details, planning, research, sequence, sources, structure

Prologue: Opening Discussion

Displayed on the whiteboard there could be a map of the Globe and a set of labels; this is included as the PowerPoint The Great Globe Itself (available in the Download section at the bottom of this page and in the Student Booklet). Students could work out where the labels should go. Remind students that they are going to visit a typical London theatre in the 1590s. What kind of person are they? How much money can they afford to spend on a seat? Where will they sit? Hear perspectives from different students in role. Ask students to make notes about their ‘character’.

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) A funny thing happened on my way to the theatre…

Ask students to imagine that they have bumped into a friend and that they are discussing their journeys to the theatre. Drawing on their research from the previous lesson, students could now form new ‘expert’ groups (representing all of the different topics covered). They should then prepare six tableaux images that show aspects of what their journey towards Shoreditch to watch Romeo and Juliet involved. Ask students to make notes on their planning sheet (in the Student Booklet).

2) Visualisation activity

Your job here is to conjure the atmosphere of a visit to the Globe in Shakespeare’s time. This could be achieved through watching a brief extract of Shakespeare in Love or by reading another extract from Jim Bradbury’s Shakespeare and His Theatre (available in the Student Booklet). This extract invites the reader/listener to imagine that they about to go to see a production of Julius Caesar at the Globe in 1599. Ask students to make further notes on their planning sheet and add in these extra thoughts (which could be arranged around the room for students to find):

- Students will be writing about going to see Romeo and Juliet in around 1595.

- Queen Elizabeth is the reigning monarch.

- We believe that Romeo and Juliet was a very popular play from its earliest performances.

- The Globe Theatre didn’t yet exist but early performances were probably staged at the Theatre and the Curtain in Shoreditch.

- Richard Burbage may have been the first actor to play Romeo.

- Juliet would have been played by a boy/young man, as would all female parts. The first actor to play Juliet might well have been the boy Robert Goffe.

- The part of Peter would have been played by Will Kemp, a celebrity actor in Elizabethan times known for his clowning and dancing.

3) Creative response

Students are going to write about visiting the theatre in Shakespeare’s time to watch a production of Romeo and Juliet. Students should now have lots of notes and can start to sequence their ideas using the suggested structure in the Student Booklet.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

Have I written effectively about the atmosphere at the theatre in Elizabethan times?

Have I included textual details about Romeo and Juliet? Have I described my reactions to the play from the perspective of my ‘character’?

Suggested plenary activity…

Peer and self assessment of imaginative writing

Asides: Further Resources

- Students could consult additional sources for their research such as Bill Bryson’sShakespeare (Chapter 4: In London) and our factsheet about Shakespeare's London: shakespearesglobe.com/uploads/files/2015/04/london.pdf

- Will Kemp was one of the star attractions of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, although the part he played – Peter, the Capulets’ servant – does not have many lines in the script. Clowns often said more than the author wrote, improvising anew every performance. Will Kemp would also have dominated the jig that ended every play, a feature that was extremely popular with audiences.

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

The imaginative writing (an account of a visit to see Romeo and Juliet) can be assessed for writing and also for reading.