In these lessons, students will be introduced to the world that Shakespeare lived and wrote in. This will help them to build an informed overview of the social and historical contexts important to the dramatic world. Tasks include: comparing and contrasting the original Holinshed source of Macbeth; researching the London of Shakespeare's time; and imaginative writing accounts.

In order to benefit fully from these lesson plans, we recommend you use them in the following order:

- Text in Performance

- Language

- Characters

- Themes

- Contexts

If students are new to the play, we suggest you start with these introductory KS3 Lesson Plans. If you would like to teach the play in greater detail, use the advanced KS4/5 Lesson Plans.

These lesson plans are available in the Downloads section at the bottom of this page. To download resources, you must be logged in. Sign up for free to access this and other exclusive features. Activities mentioned in these resources are available in a separate downloadable 'Student Booklet', also at the bottom of this page. The 'Teachers' Guide' download explains how best to use Teaching Shakespeare and also contains a bibliography and appendices referencing the resources used throughout.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I research Shakespeare’s life with a particular focus on the period when Macbeth was written and first performed?

Can I put forward my views confidently and convincingly in a class debate?

Key words: argument, author, biography, contemporary, counter-argument, debate, motion, portrait, research

Prologue: Opening Discussion

Despite being a well known name in literature, Shakespeare doesn’t have a very well known face! There is some conjecture as to what the Bard actually looked like. Students imagine they have been asked to choose a portrait to be used as the front cover of a new book about Shakespeare. They can then look up various pictures of Shakespeare online and choose the one which they would like to use for the cover. Have a feedback session where students will argue the case for their chosen picture, with pros and cons. Then vote on which cover to use. Below is an example of a picture they may use and its respective pro and con:

1) The Droeshout portrait

Pro: Fellow playwright Ben Jonson said this portrait was a good likeness of Shakespeare.

Con: Ben Jonson may not have actually seen this portrait.

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) Why study Shakespeare?

The idea is to open up a broad, frank and open-ended discussion about Shakespeare. This kind of activity could work very well as an orientation exercise at the beginning of a unit of work.

Some ideas:

- Students could be shown ‘My Shakespeare: a new poem by Kate Tempest’ (youtube.com/watch?v=i_auc2Z67OM) and discuss the ideas raised in it.

- Students could gather the viewpoints of other students, ex-students, teachers and others in relation to studying Shakespeare.

- Students could create a large collage about Shakespeare’s continuing influence on our language and in our lives today.

- Students could write their expectations about studying Shakespeare on slips of paper to be returned to them at the end of the unit. Students could then compare their predictions with their actual experiences!

2) Timeline

Students could be shown a timeline of Shakespeare’s life. It divides Shakespeare’s life into: Early Years (1564-1589); Freelance Writer (1589-1594); The Lord Chamberlain’s Man (1594-1603); The King’s Man (1603-1613); Final Years (1613-1616). Students ‘zoom’ in on the portion of Shakespeare’s life when Macbeth is written and performed and extract some key pieces of information for a Macbeth in context fact file. They should find information about biographical and historical events, the existence of the Globe and other London theatres, and other works by Shakespeare.

3) Debate

The class prepares and holds a formal debate. The motion is “The more we discover about Shakespeare the man, the more we can appreciate Shakespeare the playwright” and students should spend some time researching and planning their contributions. The class appoints a chair and the motion is proposed and opposed by the first pair of speakers, before a second member of each team also has the chance to add to their team’s case. Points and questions can then be taken from the floor, before the opposing and proposing teams sum up and a vote takes place.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

What do I now know about Shakespeare’s life and times around the time he wrote Macbeth?

How did I find these things out?

How important is it to know about a writer’s life in order to understand and enjoy that writer’s work?

Suggested plenary activity…

Students write up their own view about the motion discussed, taking into account the arguments and counter-arguments they have heard.

Asides: Further Resources

- Students might like to read about the latest portrait to be found that may or may not be Shakespeare, an image found in a botanical book called The Herball from 1598: telegraph.co.uk

- A list of recommended reading for students or book box for when they are researching what we know about Shakespeare’s life (also why we know so little) could include Anna Claybourne’s World of Shakespeare, Bill Bryson’s Shakespeare and Ben Crystal’s Shakespeare on Toast.

- Students might be aware of controversies about Shakespeare’s true identity and whether he wrote all of the plays! The film Anonymous and book Contested Will are useful sources about these debates. As far as Macbeth is concerned, the character of Hecate and one of the witches’ songs are widely considered to be the work of Shakespeare’s contemporary Thomas Middleton.

Epilogue: Teachers' Note

Students’ debate speeches and other contributions could be assessed for speaking, listening and writing too.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I investigate Shakespeare’s influences and inspiration for Macbeth?

Can I explain how Shakespeare made the story his own?

Prologue: Opening Discussion

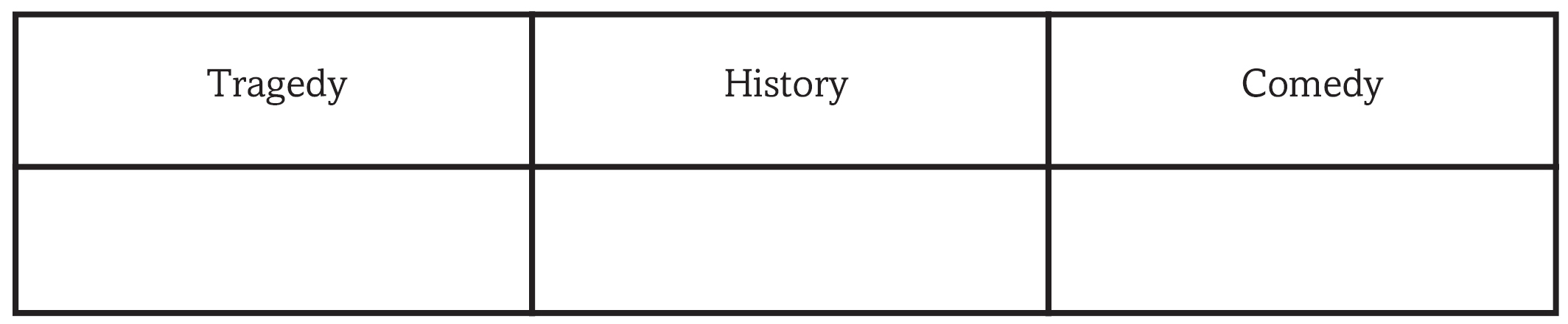

Check for students’ understanding of the word genre and of the different genres of Shakespeare’s plays. Explain that Macbeth is classified as a ‘tragedy’. Ask students to fill in the following table in the Student Booklet with their ideas about Macbeth in relation to any of these three Shakespearean genres. What do students know about Macbeth that makes it a tragedy? Can students think of anything about Macbeth that is comical or historical?

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) Macbeth, King of Alba

Explain to students that Macbeth was a real Scottish king but that Shakespeare mixed fact and fiction in his play. Students could create a Scottish kings timeline about Duncan, Macbeth and Malcolm and a fact file about Macbeth by exploring websites such as:

Afterwards, students could start to pick out any differences they have spotted between the historical Macbeth and the fictional one.

2) Compare and contrast

Shakespeare’s historical source for Macbeth and some of his other plays too was Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland. The following activity supports students in obtaining an overview of how Shakespeare’s play compares with this source material and reflecting on the reasons for the changes. Students should read the questions in the Student Booklet and plan an interview with Shakespeare. This could be done as a whole class (with you taking on the role of Shakespeare), or in small groups with a student in the hotseat.

3) Recent events

Only a year before Macbeth was written and performed, the Gunpowder Plot took place, an attempt – that failed – to murder the king. The similarities with Macbeth would not have been lost on audiences at the time. Prepare a book box and quiz or a webquest for students to support their investigation of multiple sources of information about the Gunpowder Plot. Assign questions or topics to help students focus on scanning texts to find what is relevant, and reading closely to retrieve the precise information required. Students could work in groups, allocating questions to various members who report back and pool their findings in the form of a short class presentation.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

What inspired and influenced Macbeth?

How did Shakespeare adapt and shape his sources and influences to make them his own?

Why did he do this?

Suggested plenary activity…

Students think about what it would be like to watch a performance of Macbeth in Shakespeare’s time. Students should explain in their own words something about the play that would be exciting and something about the play that would be topical.

Aside: Further Resource

- What did Shakespeare, and the people that he was writing for, think a tragedy was? Students might like to read this essay: 2011.playingshakespeare.org/themes-and-issues/tragedy.

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

The Key Stage 4 materials in the Historical and Social Context section can be used for a more in-depth comparison of Holinshed and Shakespeare, including a direct comparison of extracts from the two texts.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I establish how much I know about London in Shakespeare’s time and what I would like to find out?

Can I apply what I have learned in a creative task, and ‘step into the shoes’ of someone visiting the theatre in Shakespeare’s time?

Key words: atmosphere, empathy, glossary, questions, research, sources, topics

Prologue: Opening Discussion

Explain to students that over the next two lessons they are going to travel back in time to 1606, to one of the very first productions of Macbeth. London was by far the biggest town in England and an attractive place to young men like William Shakespeare, who arrived there to make his fortune some time between 1592 and 1594. Create a brainstorm from students’ prior knowledge and impressions of London at this time.

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) Shakespeare’s London

Students work in small groups discovering information about London life in Shakespeare’s time on a particular topic assigned to them. The topics are:

- entertainment;

- crime and punishment;

- transport;

- shops and trades;

- clothing;

- buildings;

- poverty;

- hygiene;

- risks and dangers.

The text ‘Shakespeare’s London’ by Jim Bradbury appears in the Student Booklet. Students will also need highlighter pens.

2) Theatre glossary

Explain that theatres were outside the walls of the City of London on the south bank of the River Thames. This meant that they were outside the jurisdiction of the Puritan city fathers. Here people would find bear pits, brothels and theatres. The Globe Theatre was built in 1599.

Students are going to compile their own glossary about theatres in Shakespeare’s time, the template for which can be found in the Student Booklet. Divide up the words among the group and ask them to predict what they think the word means in the context of Shakespeare’s theatre before looking it up here: shakespearesglobe.com/discovery-space/adopt-an-actor/glossary.

attic, cabbage, discovery space, frons scenae, gentlemen’s boxes, groundlings, heavens, hell, iambic pentameter, jig, lord chamberlain’s men, in the round, lords’ rooms, musicians’ gallery, pillars, thrust stage, ring house, traps, vomitorium, yard

Take feedback from students, including hearing about words that have a specific meaning in this context, but which have a different or more general meaning outside this context.

3) Publicising the play

Students should imagine that they are trying to sell tickets for Macbeth to passers-by on a rainy afternoon in 1606. How can they encourage people to come inside the theatre to see Macbeth? Students should devise publicity slogans and share them. If students have time, they could turn their slogans into printed handbills for homework.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

What would the atmosphere have been like on Bankside in 1606?

What do I think drew people to the theatre?

What do I think were the challenges involved in putting on a play?

Suggested plenary activity…

Divide students into groups of three, with each student taking on a different role. Students apply what they have learned today to an empathy task in which they wonder about what it would be like to be an actor, a ticket-seller and a playwright just before the show begins. If there is time, one or two groups could perform their role plays.

Aside: Further Resource

- The cloze activity in the Student Booklet will help students build a picture of what a visit to the theatre in Shakespeare’s time would have been like. Answers are provided in the Lesson Plan download at the bottom of this page.

By 1600 London theatres could take up to ____1_____ people for the most popular plays. With several theatres offering plays most afternoons, this meant between ____2_____ and 20,000 people a week going to London theatres. With such large audiences, plays only had short runs and then had to be replaced. Between 1560 and 1640 about 3,000 new plays were written. To attract the crowds, these plays often re-told famous stories from the past, and they used violence, music and humour to keep people’s attention. This was vital because, if audiences didn’t like a play, they made their feelings known. In 1629, a visiting French company were hissed and ____3_____ from the stage. This was because the company used ____4_____ to play the female roles, something which outraged the audience.

In open air theatres the cheapest price was only 1 penny which bought you a place amongst the ____5_____ standing in the ‘yard’ around the stage. (There were 240 pennies in £1.) For another penny, you could have a bench seat in the lower galleries which surrounded the yard. Or for a penny or so more, you could sit more comfortably on a cushion. The most expensive seats would have been in the ____6_____. Admission to the indoor theatres started at 6 pence.

The groundlings were very close to the action on stage. They could buy food and drink during the performance – ____7_____ (apples), oranges, nuts, gingerbread and ale. But there were no ____8_____ and the floor they stood on was probably just sand, ash or covered in ____9_____.

In Shakespeare’s day, as people came into the theatre they had to put their money in a ____10_____. So the place where audiences pay became known as the box office.

groundlings toilets Lord’s Rooms 10,000 women

pippin-pelted box pippins 3,000 nutshells

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

This lesson is designed to prepare students for the imaginative writing task in the next lesson.

Key Questions for Students:

Can I establish how much I know about visiting the theatre in Shakespeare’s time and what I would like to find out?

Can I imagine and describe what it would have been like to be an audience member at an early performance of Macbeth?

Key words: atmosphere, empathy, details, planning, research, sequence, sources, structure

Prologue: Opening Discussion

Displayed on the whiteboard there could be a map of the Globe and a set of labels; this is included in the PowerPoint The Great Globe Itself (available in the Download section at the bottom of this page and in the Student Booklet). Students could work out where the labels should go. Remind students that they are going to visit the Globe as it was in 1606. What kind of person are they? How much money can they afford to spend on a seat? Where will they sit? Hear perspectives from different students in role. Ask students to make notes about their ‘character’ on a planning sheet in the Student Booklet.

Enter the Players: Group Tasks

1) A funny thing happened on my way to the theatre…

Ask students to imagine that they have bumped into a friend and that they are discussing their journeys to the theatre. Drawing on their research from the previous lesson, students could now form new ‘expert’ groups (representing all of the different topics covered). They should then prepare six tableaux images that show aspects of what their journey towards Bankside to watch Macbeth involved. Ask students to make notes on their planning sheet (in the Student Booklet).

2) Visualisation activity

Your role here is to conjure the atmosphere of a visit to the Globe in Shakspeare’s time. This could be achieved through watching a brief extract of Shakespeare in Love or by reading another extract from Jim Bradbury’s Shakespeare and His Theatre (available in the Student Booklet). This invites the reader/listener to imagine that they are about to go to see a production of Julius Caesar at the Globe in 1599. Ask students to make further notes on their planning sheet and add in these extra thoughts (which could be arranged around the room for students to find):

- Remember you will be writing about going to see Macbeth in 1606.

- By then, Queen Elizabeth was dead and King James I was on the throne.

- It was thought at that time that James I was directly descended from Banquo.

- King James was very interested in witchcraft and it was a fascinating and frightening subject to many people.

- Only a year earlier, King James had narrowly missed being assassinated in the Gunpowder Plot.

- We believe that Macbeth was a very popular play from its earliest performances.

- Richard Burbage may have been the first actor to play Macbeth.

3) Creative response

Students are going to write about visiting the Globe Theatre in Shakespeare’s time to watch a production of Macbeth. Students should now have lots of notes on their planning page (in the Student Booklet), and can start to sequence their ideas using the suggested structure on the second half of the handout.

Exeunt: Closing Questions for Students

Have I written effectively about the atmosphere at the Globe?

Have I included textual details about Macbeth?

Have I described my reactions to the play from the perspective of my ‘character’?

Suggested plenary activity…

Peer and self assessment of imaginative writing

Aside: Further Resource

- Students could consult additional sources for their research such as Bill Bryson’s Shakespeare (Chapter 4: In London) and our factsheet about Shakespeare's London: shakespearesglobe.com/uploads/files/2015/04/london.pdf

Epilogue: Teacher's Note

The imaginative writing task (an account of a visit to see Macbeth) can be assessed for writing and also for reading.